January 27 2018 marked 100 years to the day that Isaac Edward Sampson died in combat on the Western Front in World War I. This is the article I wrote on that anniversary

Private Isaac Edward Sampson

When Isaac Edward Sampson was a youngster, he acquired a reputation as a sharpshooter. The legend was that you could flick a tickey up in the air and he would hit it with a shot from his rifle. It was a reputation that would eventually cost him his life.

He was the brother of my grandmother, Edna Gwendoline Sampson, a strict matron of the old school, a teacher who was an adherent of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union which sought to stamp out the scourge of alcohol.

To us, she was granny, who made white bread and served it with homemade butter and homemade apricot jam.

When the First World War broke out, South Africa, a member of the Commonwealth, went to war and young men such as Eddie – as he was known – enlisted.

As a member of the South African Infantry’s 4th Regiment – the South African Scottish – he would find himself on the brutal Western Front in France.

He would participate in what historians regard as the first “industrial war”. Hundreds of thousands of troops would fight from trench to trench amid a massive bombardment of shells, sniper fire and disease, with gains and losses measured in meters and countless lives.

In January 1918, Eddie was in the thick of this industrial war as territory changed hands in a series of heavy encounters.

Fins and Sorel on Google Maps

At the beginning of April 1917, two small villages in France were captured from the Germans. Fins and Sorel would be held until March 23 1918, when the final German offensive of the war would take them back and hold them until September.

Between April 1917 and March 1918, this ground was held by the South Africans and the 6th KSOB – King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

On January 27 1918, facing a German onslaught, Eddie was killed in action.

The exact circumstances of his death are not recorded in the most reliable history, John Buchan’s The South African Forces in France, which plots the movements of troops from day to day.

Buchan records that on January 13:

The Brigade came out of the line, and for ten days was billeted in the villages of Moislains, Heudicourt, Fins, and Sorel-le-Grand.

On the 23rd the 2nd and 3rd Regiments moved again into the line to relieve units of the 26th Brigade, and the 1st and 4th Regiments followed the next day. The relief was carried out without casualties. When the Brigade arrived at Heudicourt on 4th December it numbered 148 officers and 3621 other ranks. By January 23rd its total strength had shrunk to 79 officers and 1,661 men. On the last day of January all four battalions came out of the front trenches, and were moved to a back area for much needed month’s rest.

Three more days and Edward would have had a month’s rest.

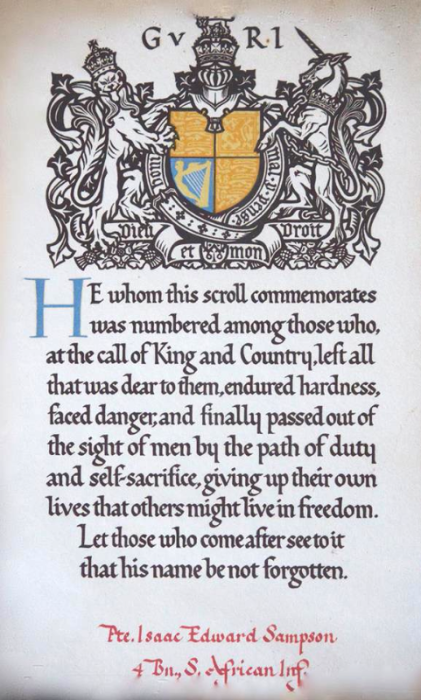

The family of each soldier who fell received a scroll

The photograph of Isaac Edward Sampson, presumably taken on his enlistment, shows a well-groomed young man who seems impossibly young for a soldier.

The sepia-toned picture, in its dark wooden frame, was a constant presence when I was growing up. It hung in our dining room next to the commemorative scroll which was sent to his family by King George V.

When I was young, it was an image that invoked fear. It shocked me that such a young man could have died so far away on a foreign field.

He had died a noble death. I quietly resolved that I would not die an ignoble one in the brown uniform of the South African Defence Force. As I reached conscription age, I took a stance against military service. I had political motives, but I was also afraid of ending up as a photograph on the wall.

Then, as I moved away to study and work elsewhere, the sepia picture faded along with the threat of conscription.

When my father retired and moved to Port Elizabeth, he took the picture with him, and it was displayed in his lounge next to the scroll.

Perhaps it’s what happens when you grow older, but I began to take an interest in Isaac Edward Sampson once more.

I was visiting my father – then in his 80s – when I asked him about the man in the photograph. He told me the story of his reputation as a marksman.

Then he told me how Eddie had died. The family legend was that, because of his sharpshooting skills, he had been called on in a moment of dire need. When his unit came under attack, he was asked to climb a tree and hold off the advancing enemy with sniper fire.

It was a suicide mission.

The guide to the Sorel-le-Grand cemetery issued in 1928. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

There was more. Granny told Dad that her brother had left home because his parents Charles Edward Sampson and Mary Ann Fisher, did not have a happy marriage. They would eventually separate.

By one telling, their father, frequently drunk, had been intolerable to live with. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union would be her response. Eddie chose enlistment and the possibility of death over life with an aggressive alcoholic.

While I digested this insight, Dad went into his bedroom and emerged with a booklet on the cemetery where Edward was buried. It listed all the dead and provided a map so that visitors could find a particular grave.

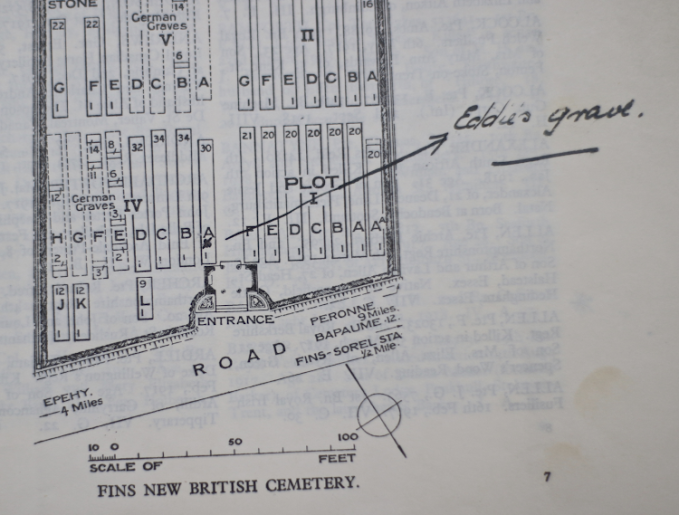

Isaac Edward Sampson was buried in the Fins New British Cemetery, Sorel-Le-Grande. Someone, perhaps Granny, had marked the exact location of the grave on the cemetery map.

Map from the guide issued in 1928 with the exact location of ‘Eddie’s grave’. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

The South Africa War Graves Project lists the South Africans buried at Sorel-Le-Grande and, for a small fee, provides photographs of the graves. I obtained a picture of Eddie’s gravestone.

The gravestone in the Fins New British Cemetary in Sorel-le-Grande, France. Picture: SA WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission description of that cemetery tells the story of the changing front in Edward’s final days.

The cemetery was used by the British and Commonwealth forces who buried 590 dead until March 1918. Then, it was used by the Germans who added 255 burials – including 26 British – and then again by the British, who added 73 graves. Finally 591 more graves were added when remains buried elsewhere were “concentrated” in the cemetery. The final line of the brief history reads: “The cemetery was designed by Sir Herbert Baker”.

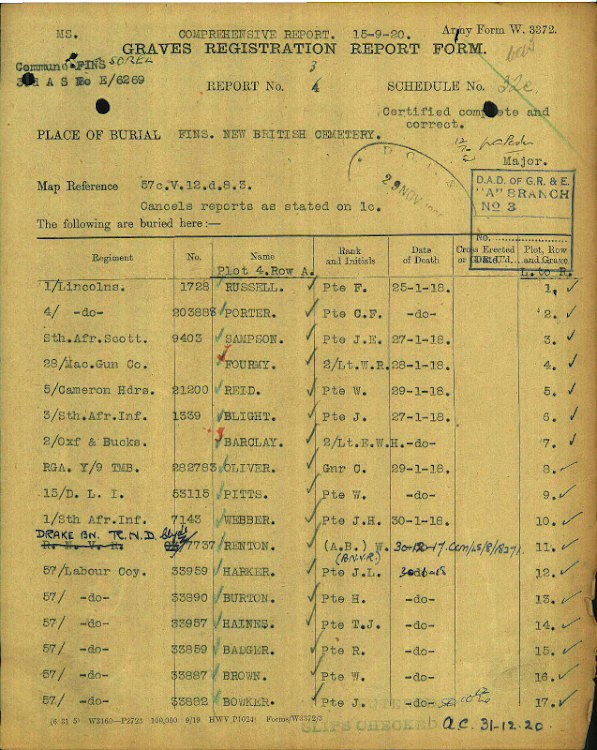

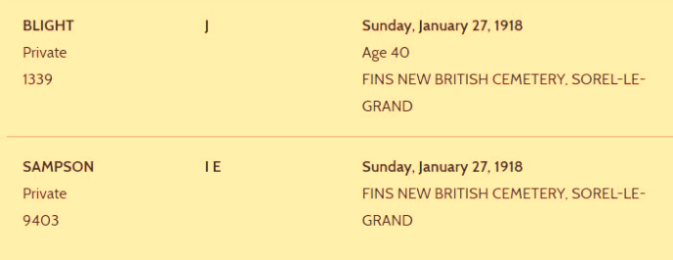

Also available were official documents relating to the graves on which my relative was listed as “JE Sampson”. Sometime between this report and the carving of his tombstone, the “J” was corrected to an “I”.

Graves registration report confirming the burial of Pte ‘J E Sampson’ of the South African Scottish. The mistake in the initials was corrected before the gravestone was erected. Image: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The SA War Graves Project web site allows you to search for “other casualties on this date”. Five South Africans had died on the same day. I was drawn to two of the names.

Joseph Blight of the 3rd Regiment died on the same day and was buried in the same cemetery. Had they died in the same battle?

The only detail offered up by the war graves project was: “Brother of Miss L. J. Blight, of Trafalgar Square, Truro, Cornwall, England.”

Privates Blight and Sampson died on the same day and are buried in the same cemetery. Image: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The grave of Frans Thomas Pinyana, who died on the same day. Picture: SA WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

The second name was that of Frans Thomas Pinyana of the South African Native Labour Corps.

He was interred at a cemetery in Seine-Maritime on France’s north coast.

I searched for and found a picture of his grave.

The stone was almost identical, with the cross, the springbok emblem and the slogan “Union is Strength”. But the stone bore an error. The surname “Pinyana” was missing.

The much smaller error of the incorrect initial on my relative’s stone had been corrected, but the glaring error on Pinyana’s stone had gone unnoticed.

The motto “Union is Strength” was on both graves, but the truth was that the union referred to – the uniting of the Boer and British republics into a single South Africa in 1910 – had formally established that there would be very little space for black South Africans in public life. Three years later, in 1913, the Native Land Act would be passed, limiting blacks to 7% of the land.

Despite this – or perhaps because of the desperation it and other exclusionary measures caused – Pinyana had enlisted.

The Victory Medal with its inscription ‘The Great War for Civilisation’

The diorama at the Queenstown museum photographed in 2014. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

But the military display was gone. I asked an official where the medal collection was stored. The answer was a blank stare.

From websites and military vendors, I began reassembling the bits and pieces of Isaac Edward Sampson’s brief military life.

I looked into the three medals that had been lost to the Queenstown museum.

They were in all probability the three nicknamed “Pip, Squeak and Wilfred” that were awarded to most soldiers who participated in the war from at least 1915.

I found some for sale online and placed an order.

The three medals arrived in the mail. They were heavier than I thought they would be. They were made back when metal was metal. The ribbons, although frayed, were surprisingly bright.

I was painfully aware that these were not his real medals and that they might not even have been the same as those he was awarded. For one thing, they had been stamped with the names of their real recipients. For another, the 1914-15 Star was awarded to those who first fought in 1915. The 1914 Star was given to those who were in it from the beginning.

I was painfully aware that these were not his real medals and that they might not even have been the same as those he was awarded. For one thing, they had been stamped with the names of their real recipients. For another, the 1914-15 Star was awarded to those who first fought in 1915. The 1914 Star was given to those who were in it from the beginning.

His regiment, the 4th South African Infantry, was known as the South African Scottish. Although hailing from the southern tip of Africa, they wore “Murray of Atholl” tartan.

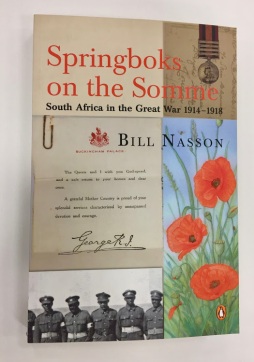

In his book Springboks on the Somme, historian Bill Nasson writes:

Bill Nasson’s book, Springboks on the Somme

The pronounced ‘military Scottishness’ of the contingent was cemented further by its operational attachment to General Henry Rawlinson’s 9th (Scottish) Division. Rawlinson, a veteran of the South African War and a soldier who had been in command in all British operations on the Western Front since 1915, made much of welcoming South African Scots or the Argylls. With South Africans often unsure of Highland or Lowland pedigrees, at times that blending was less than smooth.

I obtained collar badges for the South African Scottish identical to those warn in the sepia photograph. The left and right badges were distinguished from each other by the direction in which the arrow held in the fist pointed.

They bore the Latin motto “Mors lucrum mihi” – “Death is my reward”. The phrase originates from St Paul’s Epistle to the Philipians – “For me to live is Christ, to die is my reward”. Stripped of its religious prefix, it seemed to speak only the dark language of death.

The collar badges of the South African Scottish with the motto ‘Mors lucreum mihi’. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

Cap badge. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

I acquired a cap badge worn by the South Africans in World War I with its bilingual “Union is Strength – Eendracht Maakt Macht” motto.

When exactly had Edward enlisted?

When my father passed away last year, my sister Shivaun and I undertook that sad duty that befalls the grieving – sifting through his belongings.

Among those possessions was a tin bearing the image of Queen Victoria with the words “South Africa 1900”.

Granny’s tin of war memories. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

A South African coin stamped with ‘E SAMPSON V V MXII’. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

Inside the tin were the relics of the soldiers in her family. There was a medal purloined off an Italian soldier who had fought in Ethiopia with its blue and black striped ribbon. There were shoulder patches and collar badges.

There was a star-shaped medal from the seige of Kimberley during the South African War.

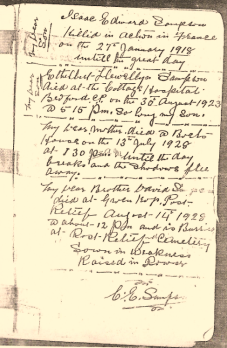

And then there were Edward’s final things.

There was a coin that had been stamped “E SAMPSON V V MX II”, with the M being an amalgamation of an X and two Is.

The number “5 5 1012” is a mystery to me. Although it has the appearance of a date, it doesn’t make sense, even if other possible numbers – XXII, for example – are substituted.

Also in the tin was a bracelet identifying “PTE E Sampson 9403 4th SA Scottish” with the letters “CONG” in the centre. This identified him as a member of the Congregationalist Church.

A bracelet identifying ‘PTE E Sampson 9403 4th SA Scottish’. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

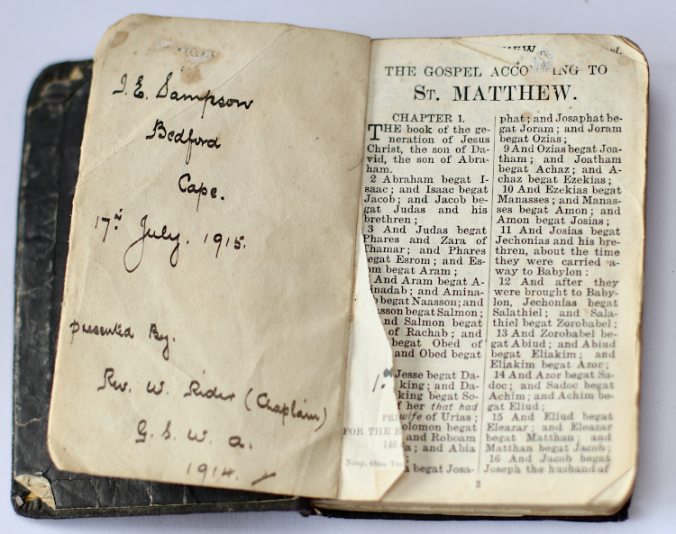

Finally, there was a clue to his length of service. A small New Testament bible which belonged to “I E Sampson, Bedford, Cape” with the date 17th July 1915.

It had been presented by “Rev W Rider (Chaplain) G.S.W.A” in 1914.

The handwriting appeared to be the same on the two inscriptions.

The New Testament bible presented to I E Sampson by ‘Rev W Rider (Chaplain) G.S.W.A 1914’. Picture: RAY HARTLEY

G.S.W.A was German South-West Africa. It now seemed possible that he had been with the South African forces from the start of the campaign in the neighbouring territory.

But why did the first inscription locate him in “Bedford, Cape” in July 1915?

Although I now know more about Edward’s military career, I know very little about who he was.

I struggled to establish how old he was. It became mandatory to register births in the Cape province only from 1905, and there is no registration certificate for Edward in the usually reliable government archives.

My uncle, Nigel Wainwright, who has researched our family tree, gave me his birth date as July 18 1893. This means he was 24-years-old when he died.

He had a few more biographical details. Although named Isaac, he was always called Edward or Eddie.

He was known as Edward and referred to as uncle Eddie. He was the oldest of ten children (7 boys and 3 girls). He was born on 18.07.1893 and was killed on 27.01.1918 Flanders while up a tree sniping. Attached is a photocopy, signed by his father, giving the date of his death. His parents were Charles Edward Sampson and Mary Ann Fisher and they lived in Bedford but were separated at some time. Charles was the sixth child of eight children and he is buried at Port Elizabeth. Mary was the seventh child of nine children and she is buried in Cathcart. Charles Edwin Vincent Sampson, Isaac Edward Sampson’s brother, bought his parents house in Bedford in about 1955.

The regiment Edward served has a monument on St Andrews Road in Parktown. I drive past it on most mornings when I take my daughter to school.

It depicts a South African soldier in full “Scottish” military gear, including a kilt and tam o’shanter beret.

The figure on the monument has its own story, which is told on The Heritage Portal:

The South African Scottish memorial in Parktown. Picture: RAY HARTLEY